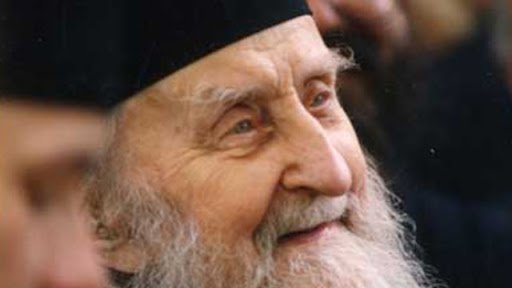

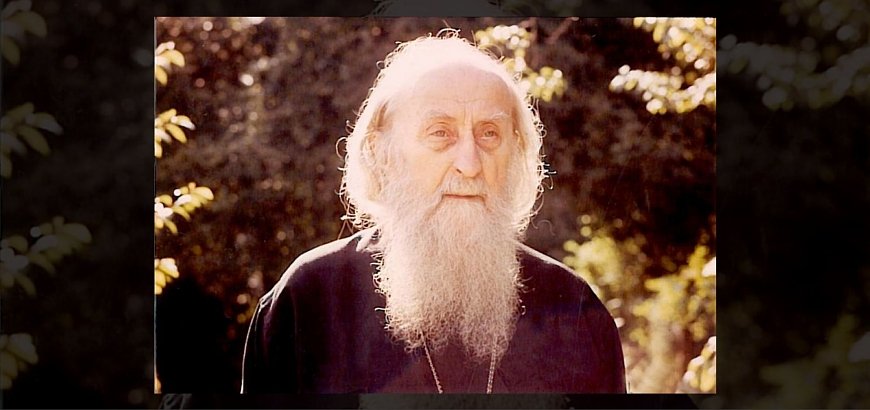

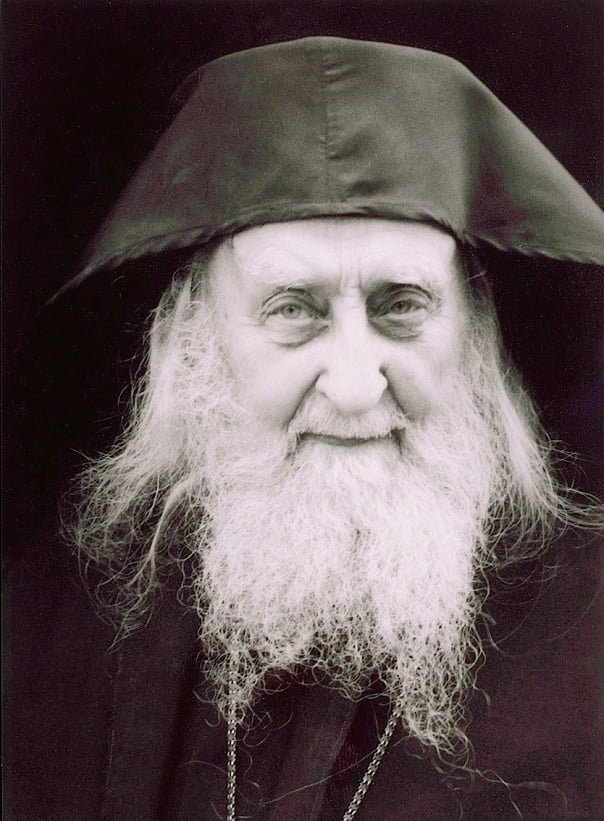

Archimandrite Sophrony was born in 1896, to Orthodox parents in Tsarist Russia. Since he was a child, he showed a rare capacity for prayer and as a young boy would participate in theological debate. Prayer entails the idea of eternity with God. In prayer, the reality of the living God is yoked with the concrete reality of earthly life. This craving, like a flame in the heart, irradiated his student days at the State School of Fine Arts in Moscow. This was the period, when a parallel speculative interest in Buddhism and the whole arena of Indian culture changed the clef of his inner life.

Eastern mysticism now seemed to him more profound than Christianity, the concept of a supra-personal absolutely more convincing than that of a Personal God. The Eastern mystic’s notion of being imparted overwhelming majesty to the transcendental. With the advent of the First World War and the subsequent Revolution in Russia, he began to think of existence itself as the cause of all suffering and so strove, through meditation, to divest himself of all visual and mental images.

The turmoil of the post- Revolutionary period made it increasingly difficult for artists to work in Russia, and in 1921 the author started to search for ways and means of emigrating to Europe - France, in particular, as the centre of the world for painters. He managed to travel through Italy, looking long at the great masterpieces of the Renaissance. After a brief stay in Berlin, he finally reached Paris, heart and soul into painting.

His career made a satisfactory start: the Salon d’ Automne accepted his first canvas and the Salon des Tuileries, the elite of the Salon d’ Automne, invited him to exhibit with them. But on the other hand, things weren’t going as he had expected. Art began to lose its significance as a means to liberation and immortality for the spirit. Even lasting fame would be but a ludicrous caricature of genuine immortality.

He must decide on a new way of living. He enrolled in the recently opened Paris Orthodox Theological Institute, in the hope of being taught how to pray, and the right attitude towards God; how to overcome one’s passions and attain divine eternity. But formal theology produced no key to the kingdom of heaven. He left Paris and made his way to Mount Athos, where men seek union with God through prayer.

Setting foot on the Holy Mountain, he kissed the ground and besought God to accept and further him in this new life. Next, he looked for a mentor, who would help extricate him from a series of apparently insoluble problems. He threw himself into prayer as fervently as he previously had in France. It was crystal-clear that if he really wanted to know God and be with Him entirely, he must dedicate himself to just that- and still more entirely than he had to painting in the old days. Prayer became both garment and breath to him, unceasing even when he slept.

After four years spent in a remote spot surrounded by mountain crags and rocks, with little water and almost no vegetation, the author assented to a suggestion from the Monastery of St Paul to move into a grotto on their land. This new cave had many advantages for an anchorite-priest. There were many hermits in the desert and they tended to settle close to one another, though hidden from sight by bounders and cliffs. Here, besides being completely isolated, there was a tiny chapel, some ten feet by seven, hewn out of the rock-face.

Winter was a hard time. The first downpour would flood the previously dry cave and then every day for perhaps six months he was obliged to scoop up and throw outside some hundred buckets of water soaking his cough. Only the little chapel stayed dry. There he could pray, and keep his books. Everywhere else was wet. Impossible to light a fire and warm up something to eat. In the end, after the third winter, failing health compelled him to abandon the grotto, which had afforded the rare privilege of living detached from the world.

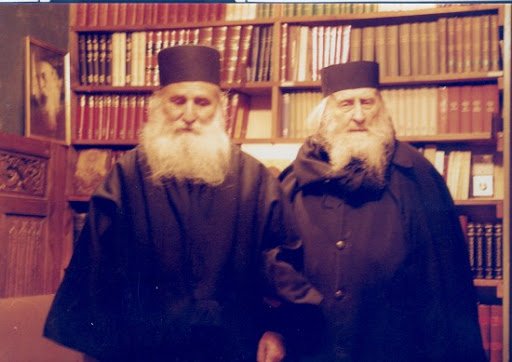

It was now that the idea came of him writing a book about Staretz Silouan, to record the precepts, which had so helped him to find his bearings in the wide expanses of the spirit by instructing him in the ways of spiritual combat. To carry out this project he would have to go back to the West- to France, where he had felt more at home than in any other country in Europe. His first intention was to stay for a year, but then he found that he would need more time. Working in difficult conditions, he fell dangerously ill and a serious operation left him an invalid, causing him to lay aside all thought of returning to a desert cave on Mount Athos.

A printed edition of his book was published in 1952. Thereafter the translations began: first into English (The Undistorted Image), then German, Greek, French, Serbian, with excerpts in still other languages. The reaction of the ascetics of the Holy Mountain was of extreme importance to the author. They confirmed the book as a true reflection of the ancient traditions of Eastern monasticism, and recognised the Staretz as spiritual heir to the great Fathers of Egypt, Palestine, Sinai and other historic schools of asceticism dating back to the beginning of the Christian era.

In 1959, accompanied by his disciples, he left again, this time reaching England, where he founded the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist. Having been a coenobitic monk and a hermit, he was now ‘a witness to the light’ (cf. John 1:7,8) at the heart of the world. In 1993, 11th July, Elder Sophrony humbly and peacefully rendered his soul to God.

Today, the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist is a place, where hundreds of pilgrims from all over the world are welcomed; it is not only one of the main centers from which Orthodoxy is radiated in the West, but also one of the strongest affirmations of the universality of Orthodoxy.